Continuing our series of blogs on the shift to electric vehicles in rural areas, our Head of Smart Mobility, Kim Smith focuses on the picturesque Devon town of Moretonhampstead to explore some of the challenges of providing charging infrastructure along its ancient narrow streets. Here, she explains some of the tools for identifying gaps in provision, and how DG Cities brings it all together, working with experts across disciplines to develop a strategy to help local residents and businesses go electric.

Moretonhampstead from Hingston Rocks, Martin Bodman

REME (Rural Electric Mobility Enabler) is an Innovate UK-funded project looking at the infrastructure challenges of supporting the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) in rural areas. As part of this work, we developed several case studies identifying areas with barriers to, and opportunities for, charging infrastructure to support both residents and visitors. Overall, the project has three primary innovation strands aimed at understanding and helping address rural EV infrastructure:

A ‘cold mapping’ tool developed by consultancy, Field Dynamics. This is a data visualisation tool which identifies areas which are, for different reasons, not attracting public charge point provision, and where a critical number of households don’t have an option for home charging.

The development of software company, Bonnet’s peer-to-peer platform to facilitate private charge point sharing (similar to an Airbnb model, but for EV chargers).

A modelling tool from EDF Energy to look at car park spaces and gauge if a conventional charging solution is feasible, or if an off-grid PV/battery charging option is more viable.

The more work we do in rural areas, the more obvious it becomes that ‘levelling up’ isn’t as straightforward as the north/south divide we so often hear about. The exclusion and high levels of deprivation already experienced in some of our rural communities leaves them very much in danger of being left behind, not least when it comes to the dash to meet net-zero transport targets.

Moretonhampstead

Moretonhampstead sits on the edge of Dartmoor at the intersection of two of the very few roads which cross the moor. It’s a small market town and forms the eastern gateway to the National Park for many of its 2.3 million annual visitors.

The town is home to a resident population of a little under 2,000, a lot of whom earn their living (directly or indirectly) from the influx of both stay and day visitors. Others rely on their cars to commute either directly or to the nearest rail link some 12 miles away. Looking at a picture of the wider area, visitor numbers on Dartmoor have remained fairly stable overall since 2003, rising from 2.3 million to 2.39 million in 2016.

Following conversations with Visit Devon and Devon County Council, a number of reasons emerged that made Moretonhampstead a good case study candidate:

Most visitors and residents use private vehicles – there is no train service and bus services to the town are limited.

On-street charging is not possible in many of the town’s narrow, busy streets.

Visitor numbers are reliably high and tourism makes a major contribution to the local economy. If we look at pre-pandemic figures, revenue generated by tourism on Dartmoor has grown from £87.5 million in 2003 to over £144 million in 2016.

Off-street parking is limited.

Internet connections can be ‘a bit sketchy’.

Devon County Council (a project partner) owns a public car park close to the town centre.

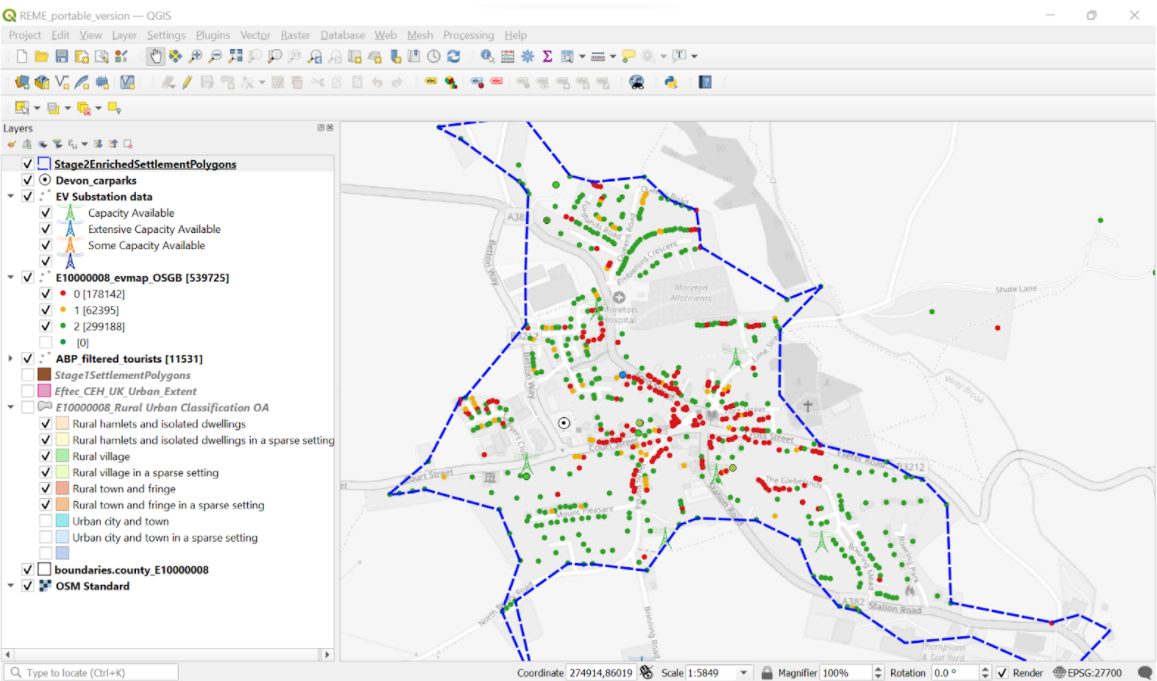

For Moretonhampstead, the first task was to create a ‘cold map’ to see if DG Cities’ initial research flagging the town as a candidate for further investigation was correct. The cold map is a data visualisation tool in which a number of variables can be overlaid, such as existing charge points, all available off-street parking (and therefore the option to charge at home), grid capacity, digital connectivity and footway/highway width. All of this can be plotted and analysed to assess opportunities for on-street provision, as well as investigating publicly or privately owned car parking space. The image below shows several of the data layers from the Moretonhampstead cold map:

Source: Field Dynamics. Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2022

With these particular layers activated, we can see:

The extent of Moretonhampstead – the hatched blue line. ONS classification data was used to define the rural settlements and the polygon boundaries were created by the project.

The red dots represent households with no on-street parking, the green dots are households with one space and the orange dots are households with space for two cars.

The Devon County Council car park is shown centre left of the map (a white dot).

Directly south of the car park is the green pylon symbol, which denotes a substation close by with good excess capacity.

What does the cold map tell us?

The outputs from the mapping showed that more than a quarter of households in Moretonhampstead had no access to off-street parking. What the town does have, however, within 200 metres of the main square, is a Devon County Council-owned, 65-space public car park - and what’s more, the grid currently has good capacity in the area.

Not shown in this image are the additional layers of digital connectivity (which is fair) and constraints for on-street provision because of limited street/footway width and seasonal congestion, for many of the ‘red dot’ households. The map gives us a clear, data-driven picture of the issues specific to the area, but the solutions are potentially applicable to other small market towns.

We knew there were barriers to EV charging in Moretonhampstead, but the cold map gave us a more accurate, data-based picture, allowing as to look at the town as a whole and zoom in at a street-by-street level. We found significant physical challenges, from the narrow streets and footways to grid capacity. We discovered that within a five-minute walk of the council’s car park, there are 225 households with no potential for a home charger – could they use chargers there? Are there other areas of the town where car parks or street width and grid capacity would accommodate public charge points? So, the next job for the project is to draw on EDF’s modelling tool to scope out the car park as a potential site for public charge points, and investigate whether they should be on- or off-grid. Although we’re coming to the end of this short project, work here isn’t finished; having the data allows us to help the council with suggestions about the location, type and speed of chargers that would be needed, both now and to facilitate the future uptake of EVs. Follow our blog for more on some of the solutions we proposed…