For the start of August, our communications lead, Sarah Simpkin shares a personal piece about her attempt to go car-free for July, and the insights that gave into the value of some of DG Cities’ projects, particularly when it comes to supporting the shift to electric vehicles in the countryside…

View of London from Blythe Hill Fields on a bike

Earlier this year, environmental charity, We Are Possible set a new challenge, Going Car Free 2022. They invited people to sign up to ditch their car for the month of July. The aim was to change participants’ behaviours by breaking the habit of driving – to give them a reason to try an alternative, even if just temporarily. I signed my family up. Given that we only used our car once in June, how hard could it be? Looking back at the month, there were a few surprises – and some new insights into the value of DG Cities’ work.

The first challenge: a wedding

The month started with a family wedding. The ceremony was in a registry office, a little over five miles from our home in south London, and the afternoon reception was in a local museum. We expected this to be one of the biggest challenges: transporting ourselves and our seven-year-old son on a hot summer’s day in our finery on bikes. But while it took a little more preparation than usual – packing a pannier the night before with snacks, locks, a change of outfit, and planning a safe route to the ceremony, reception and home again – there were benefits. We were able to incorporate a section of the car-free Waterlink Way cycle trail, a new playground, a picnic and take a breath to enjoy the view of London from the top of Blythe Hill Fields.

Our wheels for the month

For the rest of the month, we travelled everywhere by bike, train or bus. We didn’t avoid any events or change our plans. We both cycled to work, we walked our son to school, we took the train around London and we walked to the shops, ordering bulky items for delivery. The truth is, we didn’t really do anything we wouldn’t usually have done – we’re very lucky to live in an area with the services we need nearby and good public transport. We all have bikes, we are able to ride them – and we enjoy it. But then came the heatwave. The record-breaking temperatures a reminder of the urgency of the need to decarbonise and the importance of taking action as individuals.

The second challenge: the heatwave

On the hottest days of July, when London recorded 40°C for the first time, we worked from home. But there was a journey of three miles we had to take with our son. Not going wasn’t an option. Our trains were cancelled, as railways struggled to cope with high temperatures on the tracks and equipment. I read that Network Rail had planned a number of measures in advance of the heat to try to mitigate some of these impacts – maintenance teams had started painting rails white to try to reduce their temperature by 5°C to 10°C, and expansion gaps are routinely incorporated to reduce the chance of tracks buckling. Still, there was severe disruption, which lasted into the following days. We couldn’t cycle in the intense heat, there was no direct bus. And so reluctantly, we gave in – we drove. Our son was furious and demanded we do a fully car-free August to make up for it. We were disappointed too.

How might behaviours change with the climate?

Our decision to drive is just one example of an unvirtuous cycle of emissions. As the impacts of higher temperatures are more acutely felt, people’s behaviours are also likely to change – one of our neighbours talked about buying an air-conditioning unit for the first time. We all used more water than usual. We drove, we plugged in a fan. As energy demand spiked, coal-fired power stations were used to help meet grid capacity demand and avoid blackouts. But more helpfully, we also found new ways to keep cool without electricity, from using sheets to create a buffer between windows and blinds to DIY evaporative cooling techniques. A friend collected the wastewater from his shower and sink to irrigate his vegetable patch, another worked with frozen peas under their armpits.

What if there is no alternative?

Another aspect of the July challenge is talking to others about going car-free, understanding their barriers, and perhaps even persuading them to give it a try for a short time. As I mentioned, it’s easy to choose not to drive when there is a choice to make. I discussed this with friends and family, including my parents, who live in a small village with a population just over 300, almost unchanged since I left more than two decades ago. The village is five miles from the nearest town or any larger village with shops, pharmacy and doctors’ surgery. It is served by an hourly bus during the day, but the stop is on a fast A-road on the periphery of the village, half a mile from their door. A wooden bus shelter is the only sign that a post-bus used to pass through the village itself, although the ‘hopper’ service was discontinued years ago. Due to their mobility needs, active travel is not an option. For them, car-free means isolation.

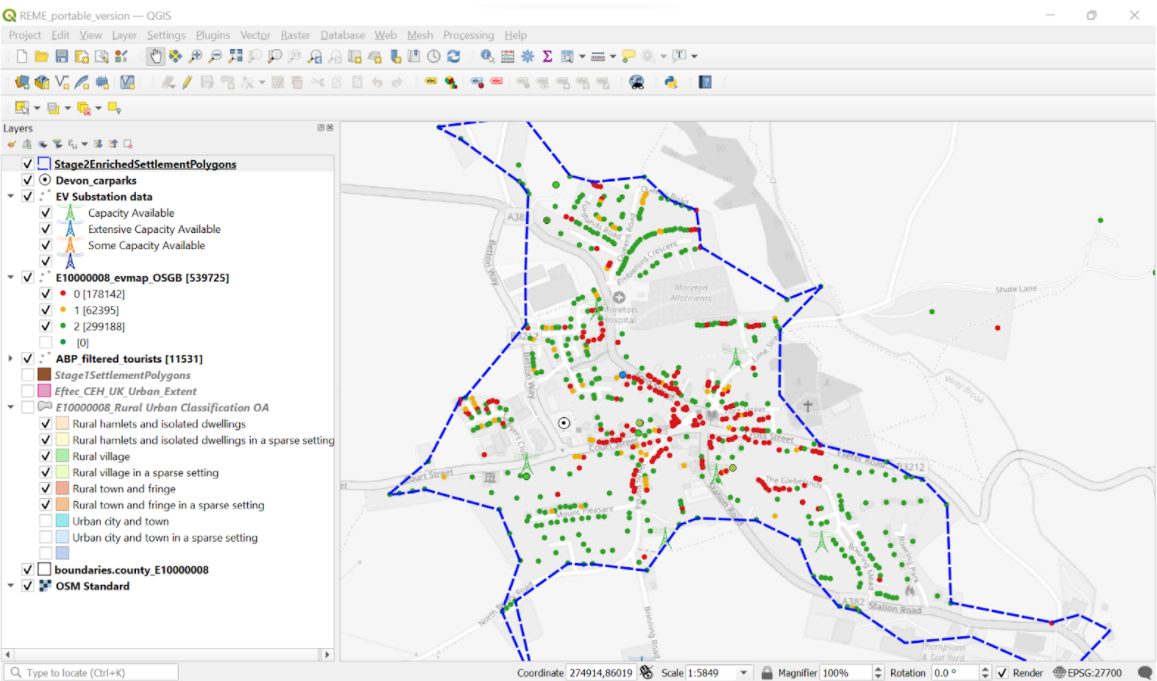

Of course, the reasons why people drive are more complex than basic needs, and the picture is different across the UK. That’s why the key focus of many decarbonisation efforts in rural areas is, understandably, in supporting the transition to electric vehicles. However, in my parents’ case, their village sometimes struggles with mobile reception, let alone any EV charging infrastructure. That’s why DG Cities work growing electric mobility in rural areas is so vital. One aspect of this is identifying gaps in provision. Working with Field Dynamics, the team developed a data visualisation tool to identify areas which are, for different reasons, not attracting public charge point investment.

The factors influencing uptake are political as well as economic. As our research shows, there is a clear link between a local authority having an EV strategy and rates of EV ownership. Right now, DG Cities and Field Dynamics are looking at places, like my parents’ village, to see how they can support local authorities in developing and implementing their strategy to meet zero-carbon targets. To learn a little more about this, here’s a film we produced to explain our approach.

What next?

Car-free July made us question why we have a car at all - just as when we bought it, its main purpose is to visit family outside London. When it reaches the end of its life, we will look at alternatives, whether that is an electric car or short-term leasing and car club for occasional use. We also considered some new micromobility solutions for the first time, like e-bikes and e-scooters, which like many in DG Cities’ survey, I had always been sceptical of. While the We Are Possible challenge didn’t force us to radically change our habits – and we failed it – it has inspired our son to hold us to account on the journeys we take. And he can be quite persuasive.